by Ganesh Sahathevan

Anwar Ibarhim's 1999 letter to IIIT founder Adbulhamid AbuSulayman republsihed on Maydan, an online publication of th AbuSulayman Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University, provides insights into his and Malaysia's friendship with HAMAS and its leaders, and the extent of that friendship. Anwar Ibrahim is now chairman of the IIIT.

My 1999 Letter from Prison to Dr. Abdulhamid AbuSulayman | by Dato Seri Anwar Ibrahim

Maydan is pleased to have the opportunity to publish for the first time—and add to the historical record—a noteworthy prison letter from Anwar Ibrahim to AbdulHamid AbuSulayman from the late 1990s. In it we have the opportunity to hear reflections on the state of intellectual trends in the international Islamic movement from one of its foremost exponents.

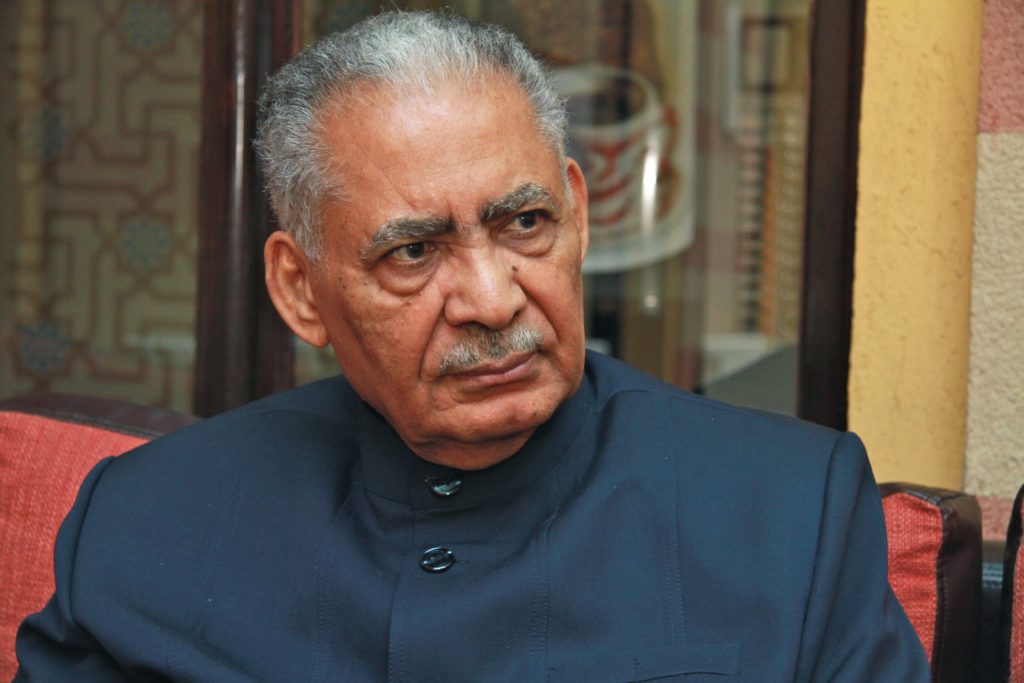

The pandemic years, beginning in 2020 and still continuing as I write this in 2022, have provided little reprieve from the reality of hardship and pain in the face of loss. I have lost far too many of my friends and colleagues over the last few years, a period which has felt more like a decade or longer. Few losses were felt with such anguish as that of my dear friend Professor Emeritus Dato’ Dr. AbdulHamid Ahmad AbuSulayman, the internationally renowned Islamic scholar, thinker, educationist and author of numerous books and articles, who passed away on 18 August 2021.

We were two men of different worlds, geographically, culturally, linguistically, and even generationally separate. Only a miracle could explain how I, a boy from a kampong (Malay village) in Penang would build a lifelong friendship with a man from Makkah. The turbulence of the 1960s and 1970s was as good a milieu as any for Dr. AbdulHamid and myself to be thrown together during the heyday of an Islamic revival movement, with hope growing out of the ashes of the colonial era. Dr. Ahmad Totonji, a master networker and doyen of public relations, instigated our many early meetings and developed our bond, which grew quickly due to our shared feelings on faith and intellectual rigor. At the time, conferences and international organisations made it easy for thinkers to intersect their ideas with common threads from across the world. Additionally, alongside a friendship I had developed with the Palestinian American philosopher Dr. Ismail Raji al-Faruqi, who visited Malaysia frequently in the 1970s, I would develop strong relationships with Dr. Taha Jabir Al-Alwani, Dr. Jamal Barzinji and Dr. Hisham Altalib and in 1981 we would go on to establish the International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT).

For us, the 1970s and 1980s meant dusk-to-dawn intellectual debates with a ferocity unseen in the normally calm nature of Malaysian interactions. A common theme in our discourses was the role of the state and educational system in instigating reform, and our circumstances as a path to reinvigorating the Ummah. By 1988, I had become Minister of Education in Malaysia and was presented with an opportunity to take all of IIIT’s theoretical discussions and put them into action by building a proper Islamic international university. But I needed help, and the only man who could help me make this dream come true was Dr. AbdulHamid.

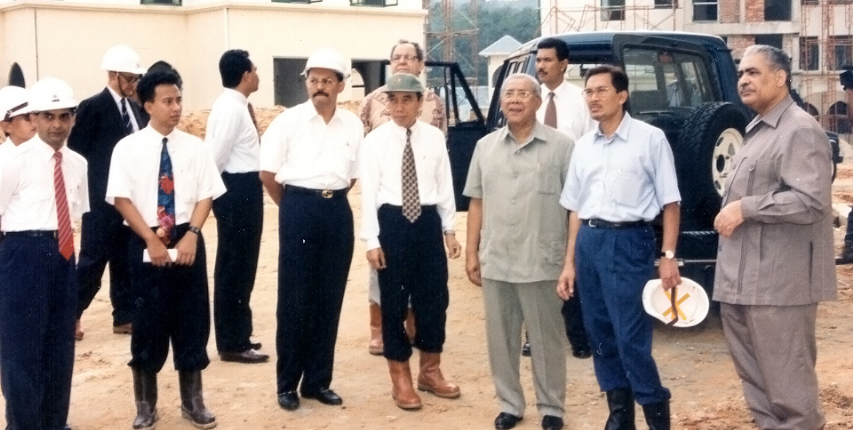

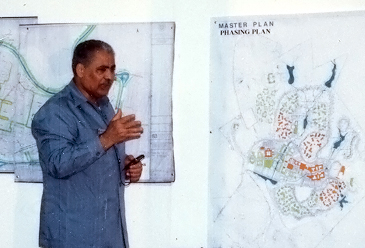

I remember making the call to Dr. AbdulHamid, who at the time was in Washington, D.C. He had thought I wanted him to give a talk or teach a course, but there had been enough lectures, now it was time to act. We had not even discussed his salary before he asked when he was expected to be in Kuala Lumpur. I had told him to make sure to at least talk to his wife Faekah first before we booked the flight. In 1989, Dr. AbdulHamid was named the second Rector of the International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM). Dr. AbdulHamid’s commitment to the growth of IIUM was matched by few others in equivalent endeavours. From the structure of the university to its physical architecture, Dr. AbdulHamid was dedicated to building not just a device for political expediency, but a model for civilisational development. At IIUM, graduates would not be churned out for the sake of profit. Graduates would be fully formed individuals, endowed not only with skills to make them leaders in their field, but moral, critical thinkers that contribute to their societies. Under his watch, IIUM flourished with graduates from Bosnia, China, Albania, Indonesia, the Philippines, and throughout Africa, who would return to hold key positions in their home countries, not to mention the Malaysian graduates, a generation of graduates unseen in the history of Malaysian higher education. He even oversaw the development of a beautiful medical campus in Kuantan.

For me, the passing of Dr. AbdulHamid was the second time I, and frankly the whole nation of Malaysia, suffered his loss. The first time was following my arrest on 20 September 1998, when Dr. AbdulHamid was unceremoniously sacked from his position as Rector of IIUM, and he and his family, who had made Malaysia their home for over a decade, were forced to leave the country. It is said that your true friends are made apparent when you are at your lowest points and Dr. AbdulHamid was there the whole way. Dr. AbdulHamid and Faekah even attended a series of demonstrations that took place at my home between my sacking from the government and my arrest – all conducted in Malay – despite not having a familiar grasp of the language. I only learned of Dr. AbdulHamid’s plight while in solitary confinement at Sungai Buloh Prison at the dawn of 1999, which happened to be during Ramadan. So, mustering the best of my handwriting (which has been panned by many spectators), I penned what would become one of my most curious of Eid addresses, the treatise before you, on scraps of paper that would be smuggled by friends from the prison to the outside, free world.

The only solace to that first farewell was that I would again be able to see and continue my stored debates with Dr. AbdulHamid once released from prison. One of the last times I would see him in person was during the launching of the $250,000 AbuSulayman International Student Fund at IIUM in April of 2019. Thanks to this fund, Dr. AbdulHamid’s mark on education in Malaysia will remain long after him. IIUM even recently renamed a department in his honour, now the AbdulHamid AbuSulayman Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences. In 2019, Dr. AbdulHamid would resign as a member of the IIIT Board of Trustees due to ill health, bookending four decades on the Board, at times serving as Chairman. In his resignation he expressed pride in IIIT’s achievements since its inception and his full confidence that the current leadership would “successfully carry forward the organisation” while stressing his genuine willingness to assist if needed.

Until I get to again see Dr. AbdulHamid, much work remains to be done not only in pursuing the realisations of our ideas, but in setting up their continuation into future generations. This letter represented the preservation of hope in an environment that was doing everything possible to extinguish it. It is fitting that we revisit it at a time of global difficulty when we must remember to keep alight the notion that things will again get better. I recall the words of the French philosopher and resistance fighter, Roger Garaudy, “it is not to bury the ashes of the dead, but to rekindle their flame.”

ANWAR IBRAHIM

Photos courtesy of the Office of Chairman Emeritus of IIIT.

Letter to Islamic University’s ex-rector | by Anwar Ibrahim

‘I choose the path of societal reform’

My dear brother AbdulHamid,

Assalamu alaikum wa rahmatullahi wa barakatuhu.

It gives me great pleasure to send you, Faekah and the rest of the family my warmest wishes and duas on the occasion of this blessed month of Ramadan. May Allah SWT accept your fasting and prayers, increase you in sabr and taqwa, and fill your lives with His blessings and peace.

It was with inexpressible sadness that I learned, from Azizah, of your departure from Malaysia and the outpouring of feeling that accompanied your farewell at the airport. A spirit as enlightened as yours, in perfect unison with the vision of IIUM, is rarely met with, and deserves utter recognition, not only for the moral characteristics and remarkable intellect you so clearly possess, but more importantly in this instance for translating speech and vision into action, propelling the growth, reputation and development of the University. Eloquent words are little more than empty speeches unless they emanate from the heart and seek to realise good for others. And thus, power guided by wisdom, you have been a central pillar in the intellectual life of the University, a driving force behind both the physical development of the Gombak Campus as well as, with foresight, the initial planning of the Kuantan Medical Campus.

Undoubtedly one of the University’s core strengths has lain in your remarkable work as Rector, making the circumstances of your resignation all the more wrong. So, I am able to write with absolute conviction that your resignation cannot be considered in any other light but as a great loss for the IIUM, and it would be wrong to avoid alluding to the true factors which lead to this decision. What particularly grieves me is the nature of the circumstances from which sprang this resignation and though I do not wish to give you pain, it is impossible for me not to give an account of them.

Since I sadly reside in solitary confinement, I have much time on my hands and am able to write a long treatise! But do not be alarmed for the sake of content which I hope will lift your spirits, but for having to read my handwriting which we both know from experience is quite atrocious. So, to spare you the ordeal of having to decipher it I am endeavouring to rewrite slowly and legibly. You will recall how you berated me once quite justifiably for your inability to read my equally as badly written Arabic, however I am leaving you no excuse this time for my English, as I feel my competency in style should remedy any shortcomings in its legibility!

With reference to this resignation, I would say firstly that I consider you a man of forbearance and wisdom, and more importantly, I am not alone in this. I trust you recognise that the machinations of a desperate despot and his handful of minions actively working to undermine you, do not reflect the real sentiments of the citizenry. Neither can any attempt on their part to discredit, minimise or even delegitimise your work or accomplishments at the University ever succeed precisely because you are recognised as the man behind so much of what has been achieved to date. Your name is associated with pious qualities and that can never be taken away from you.

Not surprisingly, the week your resignation was announced, both IIUM students (graduate and undergraduate) and staff swarmed the courthouse in protest, powerful testament to your legacy and their recognition of it, but also to make sure I knew which way their loyalties lay. It is gratifying to note that such popular sentiment for you remains alive within the University, your worth measured and richly deserved by the dedication, diligence and magnanimity you have so unstintingly shown over the years. In the process, naturally, I came to be harassed over university funding requirements.

Times such as these, let us not delude ourselves, take their toll mentally and physically. So, please look to your health. I, brother Jamal Barzinji and others have repeatedly implored you, albeit without success, to exercise regularly and engage in some form of recreational activity. Dedication should not come at the price of one’s health. I recall, one night, Faekah stating, when I telephoned to find you not at home at that late hour, that “Brother Anwar, AbdulHamid is married to the University.”

Now a little something of my own life here. The quiet solitude of prison, of solitary confinement, allows for much deep thought, spiritual reflection and prayer. We unfortunates within its walls are able to trace the various trajectories of our lives in minute detail with a thousand thoughts pressing on our minds. And one of these is my vivid recollection of those precious meetings we had, how time flies, more than twenty years ago in Riyadh as if we had begun them only yesterday. I am grateful to God for placing me in your company. In spite of our shared ideals, looking back it is a matter of importance to me how we always managed to engage in heated debates over the issues of wasilah and fiqh al-awlawiyyat (order of priorities) exchanging valuable viewpoints and ideas. Unfamiliar with loud Arab rhetoric, I remember forcing a readjustment of my subdued mannerisms – in other words, my Malayness – just so I could be heard, but impressed nonetheless by your perseverance of argument. No matter what our convictions, I fondly recall the diplomatic mastery of Dr Ahmad Totonji bringing an amicable end to our, shall we say, meeting of minds. You were always adamant in putting across your view that islah and societal reform could be meaningfully achieved only through education and knowledge or, more precisely, in the realm of thought. It’s amazing how consistent you have been, expounding those very ideas in The Crisis of the Muslim Mind, which was to be published years later. You maintain therein quite correctly that even as we marvel at the brilliance of Salahuddin al-Ayyubi’s reign, we cannot ignore the importance of the scholastic tradition and educational reform preceding it.

Sitting in prison, my introspection continuing, I would like to say that I have chosen the path of societal reform. In so doing, have had to reach a compromise of sorts, sacrificing that just balance which I have always wanted to maintain between contemplation and action. Through my involvement in ABIM, various student and youth movements, and later in government, I have always tried to generate public awareness (taw‘iyyah) of the crucial importance of ensuring al-‘adl wa al-ihsan (justice and virtue/equity) in all human affairs. It is true that I have often been conciliatory, and at times suffered criticism by colleagues, Islamists, social activists and the opposition, insisting that not all such compromises can be rationalised in the name of hikmah, or wisdom. (In fact, I intimated to you some time ago my frustrations and growing disenchantment at the excesses of the government, as well as his abhorrence of criticism, his mega-enterprises and delusions of grandeur.) Discretion is one thing, but I had to firmly draw the line when transgressions went beyond acceptable boundaries, to spread and become pervasive and rampant, in sum when religious laws and ulama suffered belittlement and abuse, when public funds were plundered to enrich families and cronies, and when such travesty of justice rose as to trample the rule of law. I have highlighted some of these issues in my earlier letters from prison, such as “From the Halls of Power to the Labyrinths of Incarceration.” (I had wanted to use “Labyrinth of Solitude,” but Octavio Paz had already used this as a title for his 1950 book length essay).

Of course, I am paying a high price for sticking to my convictions. But what are we if not men of ethics and integrity? Our status as God’s vicegerents, in positions of social responsibility, demand nothing less than unswerving fidelity to His standards not betraying them. Nor am I alone in resisting, and thus facing, the rage of an aging dictator. Unfortunately, it deeply pains me to say that my family and friends have had to suffer along with me, and it would be an understatement to say how hard it has been not to capitulate in the face of this challenge. Some have been arrested, tortured, or otherwise harassed by the Special Branch. I am not new to the dynamics of this. My own experience, in detention in 1974, taught me that it would be totally unacceptable merely to survive as a conformist while having to endure corruption and oppression. Yet, I was also a realist, aware that to pursue a reform agenda as a competent critic would result in consequences, at once challenging and beset with obstacles. Nonetheless, realist as I was, not in my worst expectations did I imagine Dr Mahathir capable of acting in such a desperate and despicable a manner as he has done; to stoop to such low levels as to allege that I am guilty of acts of treason (acting as a foreign agent), of outrageous sexual misconduct, corruption, and even to the extent of exploring the possibility of my being complicit to murder. And the fitnah and mihnah continue unabated, with character assassination and vilification by the government-controlled media. Since you left, the Inspector General of Police, Tan Sri Rahim Nor, has resigned and Dr Mahathir has relinquished his role as Minister of Home Affairs. But I intend to proceed with a civil suit against him and the IGP for physical assault, for being stripped naked, and the inhuman treatment I was subjected to under police custody. A lesson must be learnt. Citizens cannot be treated with such brutal physical abuse and ridicule.

I wish to speak honestly, the only judgement that matters to me is that of my Creator. And so, like you, I have no regrets. A deep sense of responsibility to God means we are not the personification of despair, but symbols of hope and ethical convictions that will keep resurfacing no matter how much trampled upon, to claim their rightful place for the greater good. This resilience is a gift from God, I claim no praise for it. So, I am trying to keep myself busy–with prayers and du‘a, tadarus and reading. As one enters prison one also potentially enters an arena of great spiritual growth and awareness. I am sure there is not one pious man who has been incarcerated who has not thought of prophet Yusuf. We may enter a world of complete power and control, but what sharpens paradoxically in minds is Allah’s power and control over us.

Solitary confinement can drive men mad or spiritually revive them. For me it was analogous to a desert. Deeply silent, with no distraction of plant or colour or running water, the eye of the mind roving the sand filled landscape, can see deep into the horizon with a clarity of vision that understands its own nothingness in the vastness of the dunes and, therefore, the Presence of the Creator with overwhelming spiritual transcendence, which can only lead to a transformation of the self. It is not for nothing that Prophet Muhammad’s SAW revelation arrived on barren physical soil. Those descriptions of paradise must have been felt so keenly. And sitting in the confines of my prison walls I too sensed something of what that freedom and beauty of Jannah must have entailed for those early generations of noble men. Remember Jannah is spoken of not only as a sensuous feast of the eyes and appetite but also as a realm of immense vastness. That sense of space is not often noticed but it is enticing nonetheless, as much as the other delights, and especially for the poor unfortunate hemmed in by walls and bars, only granted a little patch of sky outside.

And prison liberates the imagination like few things can. For one can bring one’s entire self, that is the heart, mind and soul to bear on ‘knowing’ God, with a concentration free from the shackles of concrete life, its objects, its swallowing up of valuable time, and its ever mounting business of matters trivial or important. The clock is ticking and few of us are listening to those precious seconds leaving us, when spiritual work remains to be done but the time span to implement Allah’s requirements is shrinking.

Solitary confinement as I have stated either fractures the soul or elevates it. For me, it allowed an opportunity to converse with God more closely and more keenly than I had done before in the busy world of my ‘outside’ political life and attendant realities. So, I availed myself of the opportunity. Deep piety can be found within prison walls if we choose God as our close companion, His mercy as He cares for us is a thing to behold. And note for those who claim that God is remote or unknowable, I would say try a stint as an inmate and pray. I felt the closeness of Allah as I prayed deeply and devoutly, the centre of my being filled with His love and mercy. All those fears and worries that relentlessly plague, circling round and round the mind like wolves hunting prey, are released through prayer into God’s hands, and their power is neutralised. I always walked away calm, self-possessed, at peace, with renewed energy and hope making plans for the future once I was released. This level of concentration on the activity of Salah gave greater inner strength and unity. Truly, prayer strips us of every ego, of every pretense, and makes us stand exposed in all our weakness before our Creator, an authentic accounting of ourselves to Him, and pure submission – the posture of the seat of our grandeur, our mind, humbly petitioning and worshipping lowered onto the ground.

Prison also affords the intellect time to read. How else could I ever have been expected to finish The Complete Works of Shakespeare, Will Durant’s Study of Philosophy, The Penguin History of the World, works of Plato and Aristotle, etc.? My old copy of Abdullah Yusuf Ali’s translation of the Qur’an resides with me within these walls, a great comfort and deeply treasured because of the short notes and references I have penned within it from before my imprisonment. I also read the tafsirs of Ibn Kathir, al-Qurtubi, Sayyid Qutb and Maulana Maududi, drinking deeply from these spiritual wells, my soul delighting in their insights. Regrettably, because of the limited number of books permitted at any given time, my hadith collection is confined to Riyad al-Salihin for the present. Nevertheless, I find my heart lightened and softened by the words of the Prophet SAW.

And I poured over the Qur’an, my great comfort and delight. Muhammad al-Ghazali’s Thematic Commentary of the Qur’an, was invaluable in the insights given into the verses. What I found remarkable was how much the Qur’an, while it revealed God, His messengers and a past history, which atheism would otherwise have buried, is also a guide that concentrates on “You.” I was exploring myself as a human being, my motivations, my purpose, the meaning I was to attach to the external world and its objects, even my future as I would have to account for myself once death lifted the veil of illusion, what the Qur’an constantly reminded me was a momentary existence. And the Qur’an, I noticed, spelled out Truth so very clearly and did not care whether this was accepted or not, for it matters not whether mankind recognises or denies the reality of God, His angels and messengers, His book. For ultimately, that Truth will prevail and man will have to give an account of himself as to why he denied what was not shrouded in mystery but in fact crystal clear. I thought of all those who had plotted to undermine morality and how quickly their works would turn to dust. And, in fact, it impressed upon me even more deeply and dramatically how much I needed to initiate plans and good works for the betterment of others, taking up the cause of societal reform with renewed impetus and vigour.

So, you will observe, my dear friend, that I have not overlooked the importance of education and the intellectual tradition behind bringing about reform. I recall my last IIIT meeting with al-Marhum Ismail al Faruqi in Virginia, which featured a debate on “Ibn Khaldun and Change,” based on Ernest Gellner’s Muslim Society. Al-Marhum Ismail, a formidable intellect, had a way of compelling me to read relevant texts before such meetings, so that discourse could have greater depth. Such encounters undoubtedly helped to further enhance my love for scholarly discourse and rekindle my passion for literature, which I have tried to share with the public, even through dry budget speeches in Parliament in the hope of introducing ‘great minds’ to the uninitiated. While trying in speeches to justify the need for reform or a reduction in taxes, for instance, I would endeavour to slip in quotes from Ibn Khaldun. I concur with Mortimer Adler in his attempt to popularise philosophy. Thus, Asian sages and reformers feature regularly in my speeches and writings, including Kung Fu Tze, Wang An Shih and the author of Thirukkural. The Asian Renaissance series (of conferences) beginning with Jose Rizal whom I consider a precursor to the Asian renaissance, was a great success. I am indebted to Cesar Adib Majul, whose seminal work on the Filipino Revolution and on Mabini, its foremost intellectual luminary, greatly influenced me. You know the tradition of the old sheikhs. Sheikh Cesar virtually forced me to go through the texts with him till about four in the morning at his residence in Manila. My only other such experience is of course with Prof. Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas. Our second conference on Muhammad Iqbal was also well attended, and his son Javed’s participation made it all the more exciting. Our plans on Jamaluddin al Afghani, Rabindranath Tagore and Sun Yat Sen have had to be temporarily shelved.

My humble apologies for digressing due to my lack of academic rigour and discipline! Back to the issue at hand. When I assumed the office of Minister of Education, I set to the task of persuading you to immediately travel to Kuala Lumpur as IIUM’s new Rector. Sensing your initial reluctance, I resorted to pricking your conscience by reminding you that instead of pontificating over the issue of education and the Islamisation of knowledge, as you had been doing, you now had the opportunity to realise those ideals, and the moral responsibility to do so. And not a word about pay or perks. It speaks volumes of your character that you ended up receiving a salary substantially lower than the renumeration you were used to as a professor in Riyadh, but which you took up without hesitation feeling it was indeed a worthy sacrifice. The appointment paid dividends for despite the limitations and constraints of the system, and with the help of selected colleagues, you exceeded all expectations; expanding IIUM’s academic programme, initiating a new university culture (causing some resentment in the process), advancing staff and academic training schemes, substantially increasing the intake of both local and foreign students and embarking upon an ambitious and impressive physical development of the new campus.

Upon reflection, we now fully appreciate how arduous, mammoth and perplexing the task was. The predominant attitude regarding education at the time was utilitarian, meaning educational institutions were operating more on a factory model approach, to churn out graduates with the necessary skills and expertise to meet the demands of industry. While it is right to expect universities to match the demands of industry, one should never lose sight of the fundamental aim of education, which is to cultivate a love of learning and scholarship, the ladhdhat al-ma‘rifah. Or, as Abul Fath al Busti has put it, “fa anta bi al-nafs, la bi al-jismi al-insan” – you are a man not because of your physique, but because of your intellect. (I used the full quote in The Asian Renaissance). And consistent with the holistic approach, the assimilation of knowledge incorporates faith (iman), Knowledge (ilm) and ethics/morality (akhlaq). Its success is contingent upon the realization of its ideals and subsequent application in daily life by our graduates. I would venture to add their commitment to disseminate truth. It is therefore incumbent upon the leadership of institutions of learning, to play a catalytic role in intellectual and societal reform. I remember recommending that all vice-chancellors read A Nation at Risk, a report on the decline of education in the United States, and Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind, exhorting for a more intellectually profound educational tradition and the relevance of morality in education. I soon began to realize, as Minister of Education in the eighties, that there would be resistance unless universities were led by competent academics and managed as a university and not as a school or adjunct of a corporation!

The university requires a resolute and firm leadership to withstand the dictates of political masters wanting to utilise education purely as a propaganda tool or to serve the requirements of corporate tsars. Otherwise, it would be in danger of an intellectually sterile leadership succumbing to all the possible dictates of the system, setting in motion a rot preventing discourse, criticism and public dialogue – all hallmarks of a functioning education system – which in turn, like a factory conveyor belt, would churn out mediocre academics and students. This reminds me of how as a young activist exasperated by the increasing number of restrictions on academic freedom and dissenting voices on campus, I alluded to the “sacred cow” which Ivan Illich speaks of in his devastating rebuke of the educational system. It is impossible to envisage dynamism, intellectual inquiry and the mushrooming of ideas under an oppressive, intolerant regime stifling real academia. Even in the Islamic education system, what has been paraded as “traditional” has gone wide of the mark of true tradition and is in fact nothing more than an “obsolete, truncated system,” as Fazlur Rahman so convincingly has argued in his Islam and Modernism. We must restore the spirit of inquiry and that of tasamuh, the tolerance of differing views. We must explore new avenues while remaining firmly rooted in authentic tradition. This is precisely why I have encouraged intellectual discourse among young academics. They must have some familiarity with philosophy while being, for instance, computer literate and academically qualified in their various disciplines.

Sheikh Taha Jabir al-Alwani, for example, expounds on the premise of turath, legacy or heritage, as a prerequisite for scholarship and, consequently, for reform. One has only to fathom the scope and depth of traditional scholarship from the comprehensive, though not necessarily exhaustive, overview of Frantz Rosenthal’s Knowledge Triumphant or George Makdisi’s The Rise of Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West, among others. To begin with, a comprehensive approach would certainly help shake one’s prejudice and ignorance concerning the subject. I would urge our students to be exposed to the works of contemporary scholars such as Dr. Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas’s Islam and Secularism, Ismail al Faruqi’s Tawhid, Seyyed Hossein Nasr’s Science and Civilisation in Islam. I am conscious of my bias for English texts, regrettably due to my rudimentary knowledge of Arabic. Our regular meetings in Riyadh and even a brilliant tutor, Dr Kamal Hassan (when I was at the University of Malaya) were not offer much help in this regard. My only consolation is that my Arabic is now at least better than most of my classmates. But credit for this is due entirely to the tutor.

Fortunately, all the major works of Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi and Sheikh Muhammad al-Ghazali have been translated into English or Malay. And their other works in Arabic have special English annotations for my personal perusal. At no time did I suggest that we ignore other Great Works, such as the collection edited by Mortimer Adler. I would even include Harold Bloom’s The Western Canon, which explores the Western literary tradition. I confess my special interest because he places Shakespeare at the centre of his Canon. But what is perplexing is our failure to enlighten our young intellectuals with our own Great Works or canon in English or Malay. The late President Zia ul-Haq’s exceptional initiative with A.K. Brohi, to undertake a major intellectual enterprise of compiling and recommending appropriate titles and to publish 100 Great Works in Islam in the English language, deserves recognition. Since I was involved with the project from the beginning together with Prof. A. Majid Mackeen, and now that the progress has been somewhat sluggish, I have intimated to our colleagues in Pakistan to collaborate in the continuation [of the project], at least for some selected titles. Similarly, the effort of the Islamic Texts Society, Cambridge in publishing some of the works of Hujjatul Islam Imam al Ghazali, including Ihya’ ‘Ulum al-Din, needs to be endorsed. I have derived inspiration from such enterprises, and I have embarked upon a similarly ambitious Karya Agong project in Malay, which would include Malay classics such as Sejarah Melayu, Islamic classics by Malay traditional scholars, other great Islamic works and the great works of the East and the West.

I reiterate my profound gratitude and appreciation for your impressive performance. And for your sacrifice and commitment. I commend you for being able to manage against the odds and particularly for exercising your utmost patience with me. Yes, I constantly react to students’ complaints and the frustrations of some members of the academic staff. Where criticisms are legitimate, we have to be magnanimous as you have so consistently demonstrated. But when we notice racist overtones to deny the fact that the very existence of the University was to serve Malaysians and the Ummah would be wrong and you are right then to react firmly.

Our universalistic approach of assimilating knowledge from both the East and West, while remaining rooted in our tradition and Islam, must be the foundation upon which we build. IIUM is a clear testimony to our resolve to maintain our independence. You would understand why some quarters in the ruling elite resent this philosophy and approach. Throughout recent history, we encounter supposed nationalists claiming strong anti-Western rhetoric on the one hand, but remaining captive to the Western mindset on the other, either in their general understanding of issues, or in their views of faith, morality and values or in their notion of laws, governance or development. This is well articulated by Sheikh Muhamad al-Ghazali as isti‘mar ruhi wa fikri, the imperialism of the soul and mind, which is devastating to the Ummah. Or, as alluded to by Malek Ben Nabi, as the characteristics of colonisibilite, the subconscious acceptance of colonialism or colonial policies. We must remain steadfast and resilient against any form of foreign domination or threat.

And we must have the courage to condemn atrocities perpetrated by any power – the Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Israel in Palestine or, recently, the United States in Iraq. But we should not remain naïve, to be duped by dictators and desperate regimes using international outrages against Muslim nations to deflect from their own shortcomings at home. Dr Mahathir is again using the distracting ploy of foreign bogeys and perceived threat to camouflage excesses and corruption. We Malaysians fought the colonial powers because of their oppression and plunder. Surely, we would not want these powers to be replaced by indigenous oppressors and squanderers. As I have indicated in The Asian Renaissance (1996): “It would be a tragedy indeed if this hard-earned freedom were to result merely in the substitution of a foreign oppressor with a domestic one” (p.62). The foreign bogey ploy is not anything new. Neither is it unique to Malaysia. Mussolini used it to dominate the Italians. He was followed by Hitler. In fact, all dictators past and present like nothing more than to maintain the perception of an ongoing threat. When they are finally defeated, they are found to have amassed enormous amounts of wealth, the accumulation of years of plunder of their people. Such is their own corruption.

I pray that the foundation that has been laid be expanded and not curtailed, advanced not derailed. I am relieved to hear of Dr Kamal’s appointment as the acting Rector. I have full confidence in him with his impressive academic credentials and experience. I am proud of our students and graduates for the credentials and experience they have gained. I pray that they will continue to carry the torch of knowledge and Islamic spirituality wherever they go. And, wherever they are, I hope they will keep calling for change and islah, in obedience to the Qur’anic verse Surah Hud: 88: “In uridu illa al-islah mastata‘tu.”

Azizah and the children join me in reciprocating your affection. Sister Faekah was such a great help and comfort to Azizah and the children. Yes, we were all baffled, initially, at the extent of acrimony and rancour, but we soon realised that their perpetrators have no bounds to their fitnah and mihnah. Did I have a choice? Should I fear retribution and fabricated charges? Without hesitation and with a clear conscience, I say that despite facing seemingly unsurmountable odds, despite the arduous nature of the task, I will continue to struggle. What helps is the spontaneity of support and overwhelming expressions of genuine concern that touches one’s soul and motivate one to continue. People are fully aware of the degenerative moral standards of the present leadership, the hypocritical lifestyles and vices which abound among those purporting morality but flouting it flagrantly. They are moreover aware of the billions amassed by leaders who are close confidantes of the leadership and who continue to be rewarded. They are not oblivious to the bailout of children and cronies. The mega projects, the majestic palaces are just too conspicuous to be erased. They have heard tape recordings of speeches abusing ulamas and denigrating religious laws and values. And now, more evidence of conspiracy at the highest level, to assassinate me politically, seems to be surfacing.

Your du‘as and those of concerned friends have helped strengthen my patience and resolve. Azizah and the children have done remarkably well. It is not easy, but I’m managing fine. These are but temporary aberrations; the dawn of a new Malaysia cannot be far off. Insha Allah, justice will come, truth will prevail, wickedness and treachery will be exposed and I shall be vindicated. As Cordelia says in King Lear: “Time shall unfold what plighted cunning hides.” Man proposes, Allah disposes! Please keep me informed of your plans. I am sorry that you were unable to visit me in prison. I certainly miss your company and Faekah’s sumptuous meals, including the kebabs and umm ma’ali. Our salaams to the family and friends. Tell Shiraz that `Ammu Anwar owes her and her husband a treat.

Alas, what a farewell – no dinners, no presents. What else can I provide from here except to express my humble gratitude from the heart – hadith al qalb bi al qalb!

Do seek the assistance of Dr. Jamal or Dr. Hisham al-Talib to decipher my writing. I can assure you that this is about the best I could offer – taking the entire Sunday. There are no other facilities available.

Again,

Eidul Mubarak

Min al-`Aidin wal faizin

Kullu `am wa antum bi khair

Wassalamu`alaikum wa rahmatullahi wa barakatuhu

Affectionately,

Akhukum fil Islam

Anwar Ibrahim

Sg Buloh Prison

23 Ramadhan 1419 / 11 January 1999

Dato’ Seri Anwar Ibrahim is the Chairman Emeritus and co-founder of the International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT), a global Muslim think-tank which aims at promoting educational reform as a means to better humanity. He was also Malaysia’s Minister of Education from 1986 to 1991, during which he introduced the National Education Philosophy in 1988 to replace the system inherited from the colonial British, besides undertaking substantial reform to improve the educational system. Anwar previously helmed the International Islamic University of Malaysia (IIUM) as its President from 1988 to 1998, with Almarhum Dr. AbdulHamid A. AbuSulayman serving as Rector, and together they set its course to be one of the renowned international universities. During his ABIM leadership, the intellectual rigour among Muslim youth was conspicuous as he commanded a plethora of Muslim intellectual giants’ works to be translated into the Malay language. Anwar also held teaching positions at Oxford University in London, Johns Hopkins University and Georgetown University in the United States. He has published a number of papers and books, as well as giving forewords to several books. His latest papers were published in Critical Muslim, titled Justice for a Praying Person (2021) and Where is the Ummah? (2021).

AbdulHamid Ahmad AbuSulayman (1936 – 18 August 2021)

Dr. AbdulHamid Ahmad AbuSulayman was born in Makkah, Saudi Arabia, in 1936, where he completed his high school education. He obtained a B.A. in Commerce from the University of Cairo (1959), an M.A. in Political Science from the University of Cairo (1963), and a Ph.D. in International Relations from the University of Pennsylvania (1973).

During his lifetime he held various positions throughout his career, including:

• Secretary for the State Planning Committee, Saudi Arabia (1963-1964).

• Founding member of the Association of Muslim Social Scientists in the United States and Canada (AMSS-US & Canada) (1972).

• Secretary-General, World Assembly of Muslim Youth, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (WAMY) (1973-1982).

• Chairperson, Department of Political Science at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (1982–1984).

• Rector, International Islamic University (IIU), Malaysia (1988–1999).

He also authored many articles and books on reforming Muslim societies, including:

• The Islamic Theory of International Relations: New Directions for Islamic Methodology and Thought.

• Crisis in the Muslim Mind.

• Marital Discord: Recapturing the Full Islamic Spirit of Human Dignity.

• Revitalizing Higher Education in the Muslim World.

• The Qur’anic Worldview: A Springboard for Cultural Reform.

• Parent-Child Relations: A Guide to Raising Children (co-author).

A full list of his academic work can be accessed here.

Dr. AbuSulayman was instrumental in organizing many international academic conferences and seminars. He was a father and a grandfather.

No comments:

Post a Comment