The IS or IS linked siege of Marawi has made life easier for Australian security agencies and their "experts" for it has provided a focal point for activity.

To paraphrase Sir Humphrey Appleby,:

“Politicians ,their security chiefs,and their "experts" like to panic. They need activity. It's their substitute for achievement.”

Of course, that activity ought not be too physically and mentally challenging;it needs to be carefully managed so that work is limited to interviews on the ABC, preferably with Virginia Trioli and Leigh Sales, who tend to do the talking and ask few questions, expect to have the "expert" confirm that they have just said.

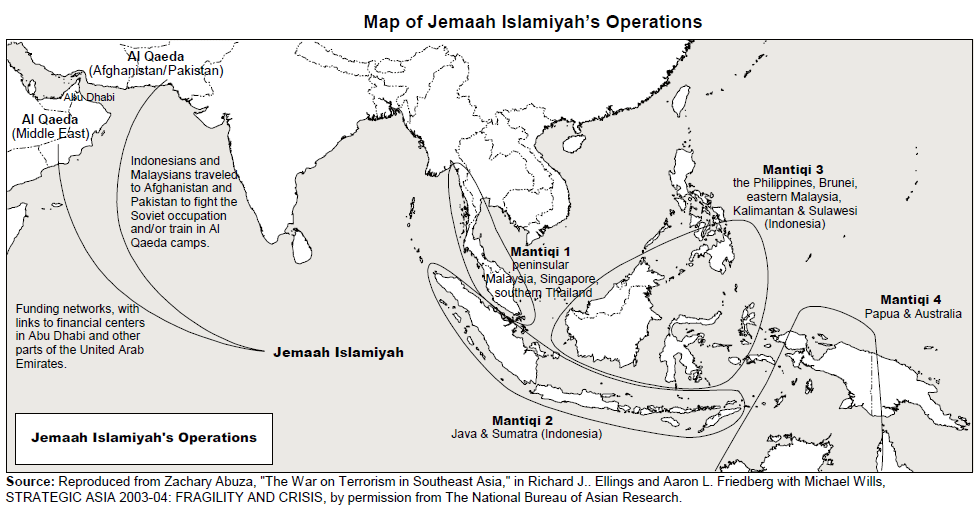

Meanwhile, in the real world, this map provides guidance to where jihadi catchments are located in this region, and from where working cells may be formed ,given the presence of strong passive support networks.While the map is based on Jemaah Islamiah activity, it does also provide a description of where passive support networks from which jihadi cells grow, are located.

(Located at https://terrortrendsbulletin.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/3.png)

For example,the Mantiqi One area which encompasses Peninsula Malaysia is the location of a number of cells, the best known being the one in Ulu Tiram which served as the base for the Bali bombers.

Marawi is clearly located in the Mantiqi 3 region,which of course includes the long established Mindanao catchment. Centrally located are the Malaysian catchments in the peninsular and Borneo,which continues to serve as a meeting point or distribution centre for manpower and supplies to the other catchments.

What ought to be of concern to Australians is the proximity of the Indonesian Mantiqi 2 catchments ,from which personnel can be easily moved onto the Australian mainland. Of greater concern is the Mantiqi 4 catchment, which includes West Papua,where jihadis are known, and remain active.

While the extension of Mantiqi 4 into Northern Australia is not of immediate concern, it would be very naive to believe that there are not in existence passive support networks

REFERENCE

(NOTE: The article below this by one G.Barton should be read for its content only.The conclusions, which are essentially a plea for further funding for "deradicalization" projects run by the author, can be ignored)

ISIS recruitment & training in Australia-An example of passive support for jihadi activities

by Ganesh Sahathevan

The article below reproduced from Sahathevan.blogspot.com should be read in conjunction with my earlier posts on the problem of passive supporters of jihadi activity.

SEP

29

ISIS recruitment & training in Australia: Government ,Muslim leaders must come clean ,

given Monash evidence

by Ganesh Sahathevan

The following is an extract from a Monash press release(see full form below) quoting "terrorism expert" and lead investigator Greg Barton:

GTReC researchers found Australian militants and terrorists frequently consulted and consumed online extremist material but other factors played far more important roles in radicalising them. Their real world social networks of friends and family, and access to individuals who fought overseas or attended terrorist training camps were far more influential in affecting their thought and behaviour than materials circulating in the virtual world.

Lead chief investigator Professor Greg Barton said relationships, in the sense of social networks, belonging, and the allure of an enhanced sense of identity, play an important role in violent.

Australian jihadis are said to be very well prepared, and the best equipped for battlefield duties. As reported in The Australian:

THERE was something about the six Australians that made them stand out. Thousands of foreigners have ventured into Syria and Iraq during the past year for their journey to jihad; but, for locals who live along the border between Turkey and Syria, this group was different. As they sat drinking coffee before making their final walk into a foreign war, these Australians stood out: they were supremely confident, well-dressed and well-resourced. “It was clear they were not rookies,” says one local who watched them sitting at the coffee shop in Turkey about 50m from the border with Syria. “They seemed to know what they were doing.”

Locals watching the group were struck by several things. First, only one of them spoke Arabic and had to translate everything for the other five. He seemed to be their leader and looked to be in his 40s while the others were younger, in their 30s. Every so often he walked away from the group to talk on the phone, as if for privacy.

Second, they were clearly well prepared; they wore new, strong-looking walking boots, a contrast to many of the bedraggled jihadists who depart from this cafe clothed in little more than their well-worn attire and a desire to join the battle for Islam between Sunnis and Shi’ites. Good shoes and bags full of supplies were low on the list of priorities for those zealots.

Observers who saw the group of Australians said they seemed prepared for a long assignment. But what stood out most was their demeanour. They were calm, confident and relaxed. Locals noticed they all had Australian passports.

They were, one local commented, physically very large — he found them intimidating — and they wore the crocheted woollen caps popular with some Muslim men. All were “very beardy”.

Understanding Terrorism in an Australian Context: Radicalisation, De-radicalisation and Counter-radicalisation

8 August 2013

The key findings from a four-year Australian Research Council-funded collaborative research project on terrorist radicalisation in Australia by researchers from Monash University’s Global Terrorism Research Centre (GTReC) will be released on Thursday 8 August.

The project, conducted in partnership with Victoria Police, Australian Federal Police, Department of Premier and Cabinet and the Victorian Department of Justice, is the most significant and in-depth examination of radicalisation undertaken in Australia.

Understanding Terrorism in an Australian Context: Radicalisation, De-radicalisation and Counter-radicalisationfocused on developing the understanding of radicalisation in an Australian context and sought international perspectives to enhance the understanding of violent extremism in Australia and relevant international threats.

Project members conducted over 100 interviews, including current and/or former violent extremists, in Australia, Indonesia, Europe, North America and elsewhere, from various ideologies (jihadist,far-right, far-left, IRA and Tamil Tigers). Also interviewed were many of the world’s leading counter-terrorism practitioners and analysts, and representatives from a variety of community groups, canvassing their attitudes on why some individuals become radicalised and ways community, government and religious stakeholders might work together to counter violent extremism.

The role of the internet and on-line materials in radicalising some individuals was also thoroughly investigated. Online sources provided both the lethal inspiration and the technical know-how for Norwegian Anders Behring Breivik’s anti-Islam motivated terrorism in Oslo and Utoya Island in July 2011, in the attack Tamerlan and Johar Tsarnaev perpetrated at the Boston Marathon in April 2013 and the brutal murder of off-duty British soldier Leigh Rigby in Woolwich, London, in May 2013.

GTReC researchers found Australian militants and terrorists frequently consulted and consumed online extremist material but other factors played far more important roles in radicalising them. Their real world social networks of friends and family, and access to individuals who fought overseas or attended terrorist training camps were far more influential in affecting their thought and behaviour than materials circulating in the virtual world.

Lead chief investigator Professor Greg Barton said relationships, in the sense of social networks, belonging, and the allure of an enhanced sense of identity, play an important role in violent extremism.

“Academics like to focus on ideas and ideology, but emotions, social bonds and experiences also play a crucial role. For many who become caught up in violent extremism social networks are much more important than ideology," Professor Barton said.

The findings also highlighted the importance of using, where possible, non-coercive measures to work with vulnerable individuals and groups to deflect and dissuade them from using violence to achieve their goals. These measures, commonly described as ‘CVE’ (countering violent extremism) initiatives, are becoming more prominent in Australia and overseas as many countries’ security services have observed that such ‘hard’ responses, by themselves, have often been ineffective, sometimes paradoxically increasing, rather than deterring the prospects of radicalising individuals. GTReC’s research highlights the effectiveness of including the social networks of radicalised or vulnerable individuals in countering violent extremism in both Australia and elsewhere.

CVE approaches prioritise interventions that are well ‘upstream’, averting problems before they are fully formed and give rise to criminal behaviour. Recognising key signs, or indicators, of radicalisation is an essential element of CVE. To this end GTReC researchers have developed a model that will enable a diverse range of practitioners to collectively recognise signs of radicalisation through observing indicative changes in behaviour, thinking and social relationships that, when occurring together and trending over time, point to reasons for concern and the need for some sort of intervention.

CVE also requires ‘downstream’ initiatives focusing on rehabilitation and helping individuals and groups disengage from violent extremism and re-engage with mainstream society. All forms of CVE require attention to both the individual and their environment.

For more information contact Glynis Smalley, Monash Media & Communications + 61 3 9903 4843 or 0408 027 848.

The following is an extract from a Monash press release(see full form below) quoting "terrorism expert" and lead investigator Greg Barton:

GTReC researchers found Australian militants and terrorists frequently consulted and consumed online extremist material but other factors played far more important roles in radicalising them. Their real world social networks of friends and family, and access to individuals who fought overseas or attended terrorist training camps were far more influential in affecting their thought and behaviour than materials circulating in the virtual world.

Lead chief investigator Professor Greg Barton said relationships, in the sense of social networks, belonging, and the allure of an enhanced sense of identity, play an important role in violent.

Australian jihadis are said to be very well prepared, and the best equipped for battlefield duties. As reported in The Australian:

THERE was something about the six Australians that made them stand out. Thousands of foreigners have ventured into Syria and Iraq during the past year for their journey to jihad; but, for locals who live along the border between Turkey and Syria, this group was different. As they sat drinking coffee before making their final walk into a foreign war, these Australians stood out: they were supremely confident, well-dressed and well-resourced. “It was clear they were not rookies,” says one local who watched them sitting at the coffee shop in Turkey about 50m from the border with Syria. “They seemed to know what they were doing.”

Locals watching the group were struck by several things. First, only one of them spoke Arabic and had to translate everything for the other five. He seemed to be their leader and looked to be in his 40s while the others were younger, in their 30s. Every so often he walked away from the group to talk on the phone, as if for privacy.

Second, they were clearly well prepared; they wore new, strong-looking walking boots, a contrast to many of the bedraggled jihadists who depart from this cafe clothed in little more than their well-worn attire and a desire to join the battle for Islam between Sunnis and Shi’ites. Good shoes and bags full of supplies were low on the list of priorities for those zealots.

Observers who saw the group of Australians said they seemed prepared for a long assignment. But what stood out most was their demeanour. They were calm, confident and relaxed. Locals noticed they all had Australian passports.

They were, one local commented, physically very large — he found them intimidating — and they wore the crocheted woollen caps popular with some Muslim men. All were “very beardy”.

(Unholy foot soldiers in a foreign fight THE AUSTRALIAN JULY 12, 2014)

It is obvious that these Australian jihadis had been trained professionally, were well funded, and had support of strong network of passive supporters. It is time for the Government, law enforcement agencies, and Muslim leaders, to tell us who these people are, and what is being done to eradicate the threat they pose this society.

END

Understanding Terrorism in an Australian Context: Radicalisation, De-radicalisation and Counter-radicalisation

8 August 2013

The key findings from a four-year Australian Research Council-funded collaborative research project on terrorist radicalisation in Australia by researchers from Monash University’s Global Terrorism Research Centre (GTReC) will be released on Thursday 8 August.

The project, conducted in partnership with Victoria Police, Australian Federal Police, Department of Premier and Cabinet and the Victorian Department of Justice, is the most significant and in-depth examination of radicalisation undertaken in Australia.

Understanding Terrorism in an Australian Context: Radicalisation, De-radicalisation and Counter-radicalisationfocused on developing the understanding of radicalisation in an Australian context and sought international perspectives to enhance the understanding of violent extremism in Australia and relevant international threats.

Project members conducted over 100 interviews, including current and/or former violent extremists, in Australia, Indonesia, Europe, North America and elsewhere, from various ideologies (jihadist,far-right, far-left, IRA and Tamil Tigers). Also interviewed were many of the world’s leading counter-terrorism practitioners and analysts, and representatives from a variety of community groups, canvassing their attitudes on why some individuals become radicalised and ways community, government and religious stakeholders might work together to counter violent extremism.

The role of the internet and on-line materials in radicalising some individuals was also thoroughly investigated. Online sources provided both the lethal inspiration and the technical know-how for Norwegian Anders Behring Breivik’s anti-Islam motivated terrorism in Oslo and Utoya Island in July 2011, in the attack Tamerlan and Johar Tsarnaev perpetrated at the Boston Marathon in April 2013 and the brutal murder of off-duty British soldier Leigh Rigby in Woolwich, London, in May 2013.

GTReC researchers found Australian militants and terrorists frequently consulted and consumed online extremist material but other factors played far more important roles in radicalising them. Their real world social networks of friends and family, and access to individuals who fought overseas or attended terrorist training camps were far more influential in affecting their thought and behaviour than materials circulating in the virtual world.

Lead chief investigator Professor Greg Barton said relationships, in the sense of social networks, belonging, and the allure of an enhanced sense of identity, play an important role in violent extremism.

“Academics like to focus on ideas and ideology, but emotions, social bonds and experiences also play a crucial role. For many who become caught up in violent extremism social networks are much more important than ideology," Professor Barton said.

The findings also highlighted the importance of using, where possible, non-coercive measures to work with vulnerable individuals and groups to deflect and dissuade them from using violence to achieve their goals. These measures, commonly described as ‘CVE’ (countering violent extremism) initiatives, are becoming more prominent in Australia and overseas as many countries’ security services have observed that such ‘hard’ responses, by themselves, have often been ineffective, sometimes paradoxically increasing, rather than deterring the prospects of radicalising individuals. GTReC’s research highlights the effectiveness of including the social networks of radicalised or vulnerable individuals in countering violent extremism in both Australia and elsewhere.

CVE approaches prioritise interventions that are well ‘upstream’, averting problems before they are fully formed and give rise to criminal behaviour. Recognising key signs, or indicators, of radicalisation is an essential element of CVE. To this end GTReC researchers have developed a model that will enable a diverse range of practitioners to collectively recognise signs of radicalisation through observing indicative changes in behaviour, thinking and social relationships that, when occurring together and trending over time, point to reasons for concern and the need for some sort of intervention.

CVE also requires ‘downstream’ initiatives focusing on rehabilitation and helping individuals and groups disengage from violent extremism and re-engage with mainstream society. All forms of CVE require attention to both the individual and their environment.

For more information contact Glynis Smalley, Monash Media & Communications + 61 3 9903 4843 or 0408 027 848.

No comments:

Post a Comment