by Ganesh Sahathevan

Here is what draws migrants to Australia, to this day, explained in clear terms by Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs (1855-1948), governor-general, judge and politician,

by Ganesh Sahathevan

Here is what draws migrants to Australia, to this day, explained in clear terms by Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs (1855-1948), governor-general, judge and politician,

by Ganesh Sahathevan

After reviewing the group's history, Wolf identified one of their most effective tactics and why it is so dangerous:

Given CAIR’s genesis, its associations with known terrorist entities and individuals, and its tactics—namely attempting to discredit anyone who dares to speak out against its organization—their cries of victimization and accusations of religious bigotry appear disingenuous.

Wolf further noted that:

In a federal court filing from December 2007, federal prosecutors described CAIR as "having conspired with other affiliates of the Muslim Brotherhood to support terrorists." The government also stated that "proof that the conspirators used deception to conceal from the American public their connections to terrorists was introduced" in the Holy Land Foundation trial.

In a footnote government prosecutors point out: “(F)rom its founding by Muslim Brotherhood leaders, CAIR conspired with other affiliates of the Muslim Brotherhood to support terrorists…”

The errors of judgement in dealing with the Islamist-Jihadist threat described above ought to disqualify Richardson from leading the Bondi Hanukkah Massacre intelligence and security review. It is likely that he will be distracted by his own historical failures, that led to the massacre.

by Ganesh Sahathevan

by Ganesh Sahathevan

According to an eyewitness, unidentified gunmen opened fire on the tourists at close range. Reports suggest the assailants fired after ascertaining the tourists’ religion. Disturbing videos show trousers of some tourists being pulled down to identify their religion.

On Tuesday, witnesses told Al Jazeera that the area was bustling with tourists. At about 2:45pm, a group of armed men in camouflage clothes emerged from a nearby forest, an official said, requesting anonymity to discuss details that security forces have not made public.

The attackers “opened indiscriminate fire at Baisaran meadow, a scenic uphill area accessible only by foot or pony rides,” the official said. Many tourists were caught off-guard as the sudden volley of bullets rang out.

Two gunmen have attacked a Jewish festival at Sydney’s popular Bondi Beach, killing at least 15 people and wounding dozens, according to Australian authorities.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said the “devastating” mass shooting on Sunday, which police are calling a “terrorist” incident, was “a targeted attack on Jewish Australians on the first day of Hanukkah”.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) reported that a “Chanukah by the Sea” event had begun at a playground near the northern end of the beach when the attack occurred at 6:47pm (07:47 GMT) near the Bondi Pavilion.

More than 1,000 people had gathered at the event, according to police.

The ABC spoke to a witness who described seeing two black-clad armed men standing on a bridge, shooting at crowds who had gathered for the event.

Camilo Diaz, a 25-year-old student from Chile, recounted hearing a long series of gunshots as the attack unfolded.

“It was shocking. It felt like 10 minutes of just bang, bang, bang,” he told the AFP news agency at the scene, adding, “It seemed like a powerful weapon”.

One of the alleged shooters, a 50-year-old man, was killed at the scene. His 24-year-old son, the second gunman, was taken into custody and is in a critical condition, Lanyon said.

Lanyon said authorities were not looking for a third person.

The police commissioner added that the 50-year-old man had six firearms licences and that six firearms were found at the scene.

“Ballistics and forensic investigation will determine whether those six firearms are the six that were licensed to that man,” he said.

Lanyon also told journalists that two active “rudimentary” explosive devices were found at the scene of the shooting.

At around 18:47 local time (07:47 GMT), New South Wales Police received reports that a number of shots had been fired at Archer Park, Bondi Beach.

A short while later, police shared their first public statement, urging anyone at the scene to take shelter and others to avoid the area.

Verified videos captured hundreds of people fleeing the beach, screaming and running as a volley of gunshots rang out.

Footage verified by the BBC appears to show two gunmen firing from a small bridge which crosses from the car park on Campbell Parade towards Bondi Beach.

A 10-year-old girl was among the fifteen people killed in the shooting, according to New South Wales Police.

The ages of the victims ranges from 10 to 87 years old. No further details have been provided.

The family of British-born Rabbi Eli Schlanger, 41, has told the BBC that he is among the dead.

Schlanger's cousin, Rabbi Zalman Lewis, said he was "vivacious, energetic, full of life and a very warm outgoing person who loved to help people".

Israeli media - citing Israel's foreign ministry - reported that an Israeli citizen was also killed.

French citizen Dan Elkayam has also been identified as a victim of the attack.

Police say the gunmen were father and son aged 50 and 24, New South Wales Police Commissioner Mal Lanyon told a news conference on Monday morning.

The 50-year-old male was a licenced firearms holder. He was linked to six firearms, all of which were believed to have been used in the Bondi Beach attack, Lanyon said.

And finally from the Times Of India:

A father and son, identified as Sajid and Naveed Akram, carried out a deadly mass shooting at Sydney's Bondi Beach during a Jewish festival, killing 16, including gunman. Authorities declared the incident a terrorist act, with IS flags found and one attacker previously known to intelligence agencies.

Liam Collins, Jayson Geroux, and John Spencer | 11.26.25

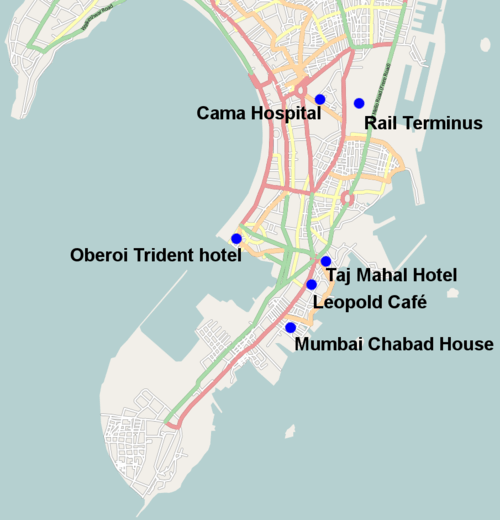

Authors’ note: Many of the details included in this case study were learned during a 2019 trip to Mumbai by two of the authors, Liam Collins and John Spencer, during which they had the opportunity to interview Indian government officials, military personnel, and witnesses to the terrorist attack and visit key sites involved in the attack.

The Mumbai terrorist attacks occurred from November 26 to November 29, 2008. Ten terrorists believed to be connected to the Lashkar-e-Taiba terrorist group besieged and paralyzed a city of nearly eighteen million for sixty hours while the world watched the events unfold on live television. The event is often referred to as the 26/11 attacks and is widely seen as India’s equivalent of the United States’ 9/11 attacks.

Mumbai is India’s commercial, economic, and entertainment center. In 2008, it was home to more than 17.9 million residents packed into just 603 square kilometers (233 square miles), making it one of the world’s most densely populated cities. The city sits on a north-south peninsula bordered by the Arabian Sea to its west and south and Mumbai Harbor and Thane Creek to its east. Several smaller waterways, bays, and lakes are also located throughout Mumbai. The city encompasses vast and tightly packed residential and industrial belts stretching in all directions from its urban core.

The urban terrain is dense and diverse, with high-rise hotels and office buildings situated alongside sprawling slum clusters. Many streets are barely wide enough for a single vehicle, and aside from a few major thoroughfares, the road network followed an irregular and constricted pattern that limited visibility and movement. The combination of constrained terrain, density of people and structures, and the nearly constant infrastructure projects required to support the megacity’s population make Mumbai’s traffic ranked among the worst in the world. Many commuters rely mainly on three major north-south railway corridors that formed the city’s public transit backbone. By mid-2008, these routes carried an estimated seven million passengers daily. The Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, a rail station and the city’s main rail stop, was one of the world’s busiest. All these factors produced geographic and human-made choke points that constricted transportation and movement.

The southernmost tip of the peninsula is the most densely populated part of the city and home to iconic landmarks such as the giant stone arch Gateway of India Mumbai. The terrorists would land and conduct their attacks on a small strip of land, 1,500 meters wide and 3,000 meters deep, near the southern end of the peninsula. The terrorists landed at two sites: near the fishing colony of Machhimar Nagar on the peninsula’s western side and the Sassoon Docks on its eastern side. They would ultimately attack six sites. Four of these—the Oberoi Trident Hotel, the Nariman House (Chabad Lubavitch Jewish Community Center), the Leopold Café, and the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel—were located within 1,250 meters of the landing sites. The other two sites—the Cama and Albless Hospital and the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus—were located 3,000 meters north of the landing sites.

Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), a Pakistan-based terrorist organization, is believed to be responsible for the attack. The group reportedly started reconnaissance and planning for the attacks in late 2005, if not earlier. Pakistani-American David Headley was convicted of playing a vital role in the reconnaissance of the targets and landing sites. According to his testimony, he conducted five surveillance trips to Mumbai between September 2006 and July 2008. On one visit he stayed at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, which would later be selected as one of the targets. During these trips he photographed hallways, stairwells, entrances, security posts, and choke points, recorded videos, drew schematics, and mapped service corridors and staff entry and exit routes of the different locations. He also took boat trips around the harbor, where he recorded important locations on a GPS device. After each trip, he provided these intelligence products to LeT operatives in Pakistan.

Headley also examined Mumbai’s waterfront vulnerabilities, focusing on the Machhimar Nagar fishing colony and the Sassoon Docks in the southern end of the city. These coastal neighborhoods had no formal perimeter security, minimal police presence, and high volumes of unregulated fishing traffic. Many of the residents were migrants or informal laborers, often living without proper documentation or full legal recognition by the state. These were neighborhoods where outsiders were common and police-community relations were weak. It is likely the attackers calculated that suspicious behavior would be less likely to be reported to authorities if they operated in this area.

While Headley conducted reconnaissance, LeT selected and trained the ten-person terrorist assault team, drawn from low-income communities in Pakistan’s Punjab Province. Recruits were motivated by their extremist ideology and the promise of financial compensation to their families. Having limited education and employment prospects, the promise of posthumous compensation estimated at several thousand US dollars for their families was significant. Their training occurred over several months in multiple LeT camps across Pakistan and covered small arms, grenades, map reading, room clearing, and urban combat. The training also included building confidence under pressure and hostage handling. LeT dedicated a portion of their training to maritime operations, including how to board and seize ships at sea, how to use GPS navigation equipment in small watercraft, and how to conduct covert landings in darkness. The attackers rehearsed tactical movements in mock hotel layouts and practiced assaults simulating real targets.

US and Indian investigations later concluded that the attackers received direction from handlers linked to Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), including a figure identified as “Major Iqbal,” whom they believed to be an active duty ISI officer. During the attacks, Major Iqbal and senior LeT operator Sajid Mir would command the operation from a control room in Karachi, where they could provide the attackers with real-time instructions based on television broadcasts and intercepted Indian communications.

During the first phase of the operation, the ten terrorists would infiltrate Mumbai by sea and come ashore under the cover of darkness. During the second phase, they would split into five heavily armed two-person teams (two would later join to form a team of four), to launch coordinated and nearly simultaneous attacks on six targets: the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, the Cama and Albless Hospital, the Nariman House, the Oberoi Trident Hotel, the Leopold Café, and the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel. During their movement through the city, the attackers would plant improvised explosive devices (IEDs) on street corners and in the vehicles they used to create additional chaos during their assaults. With simultaneous attacks on six targets and IEDs left in their wake, LeT sought to overwhelm Indian security forces, slow their response, and extend the operation.

During the third phase, the attackers would remain in the city, using its dense urban terrain to outmaneuver security forces and prolong the fight. It was meant to be a suicide operation, so that none of the attackers could later testify as to how the operation was planned and executed. Although it was a terrorist operation, it was also a coordinated urban battle that would be fought in the heart of a megacity.

The internal security apparatus of India in general and Mumbai in particular were underresourced and unprepared for a coordinated urban assault. Mumbai had suffered a dozen major IED bombings between 1993 and 2006, so security forces were prepared to respond to IED attacks. But they were prepared only for disaster response and recovery in which the perpetrators had long since fled, as opposed to an IED attack in which the perpetrators remained to conduct an active attack. As such, postdetonation emergency procedures were geared toward perimeter containment, the forensic gathering of evidence, investigations, and raids against the terrorist IED networks. At the time, the idea that terrorists would simultaneously attack and seize multiple sites across a city was unimaginable for Mumbai’s security forces, as it was for the security forces of many nations, just as few could have anticipated a handful of terrorists using boxcutters to hijack a plane and turn it into a suicide munition prior to 9/11.

Mumbai’s internal security structure in 2008 consisted of multiple overlapping police and paramilitary units, each with distinct roles and severe capability limitations. The Mumbai Police were the city’s primary first responders, responsible for law enforcement and initial reaction to any attack, but most officers were armed only with 7.62-millimeter self-loading rifles, .303 rifles, pistols, or lathis (batons) and had little training or equipment for close-quarters combat against automatic weapons. Within the police, the Anti-Terrorism Squad handled counterterrorism investigations, but its operational arm—the quick response teams—lacked realistic live-fire and hostage-rescue training and were fragmented across the city during the attack, weakening their ability to function as cohesive commando teams. The Maharashtra State Reserve Police Force provided additional armed manpower but was designed for crowd control and rural security tasks rather than urban combat. The Indian Navy’s Marine Commandos, based in Mumbai, were elite special operations forces capable of intervention but were not postured for rapid urban insertion and arrived piecemeal hours after the first attacks. The country’s premier counterterrorism unit, the National Security Guard, was based more than seven hundred miles away in Delhi. It required hours to mobilize, secure aircraft, and reach Mumbai.

Maritime security was equally deficient. Mumbai’s waterfront was guarded by a small number of Indian Navy patrol boats and underequipped police units that were not prepared to detect or intercept a seaborne infiltration. Local police were responsible for patrolling from the shore up to twelve nautical miles out, the Indian Coast Guard from twelve to two hundred nautical miles out, and the Indian Navy beyond that, but the system functioned poorly. For sea patrolling, India’s customs bureau was expected to provide boats and police were expected to provide staff. This patchwork arrangement resulted in serious capability gaps. Police units thus lacked high-speed boats, had limited radar or surveillance support, and received only minimal sea training, leaving them unprepared for an organized maritime approach.

The attackers departed from Karachi aboard a Pakistani-flagged cargo vessel on or about November 21, 2008. After sailing for over thirty-six hours across the Arabian Sea, the group intercepted and hijacked the forty-five-foot Indian fishing trawler Kuber close to India’s coast, on November 23. The attackers killed the crew but kept the ship’s captain, Amarsinh Solanki, alive so that he could navigate the ship to Mumbai. The ship approached the city’s coastline on the evening of November 26, blending in with regular maritime traffic and going undetected due to gaps in coastal radar coverage and a lack of coordinated maritime domain awareness. The attackers then executed Solanki and discarded identifying documents, satellite telephones, and GPS equipment to erase their trail. They then transferred their weapons, gear, and communication equipment into two small inflatable boats painted in bright yellow and orange to mimic local fishing watercraft.

Around 8:30 p.m., the attackers beached their boats at the predesignated landing sites, one group at the Machhimar Nagar fishing colony and the other at the Sassoon Docks. The day and timing of the insertion was deliberate, coinciding with a high-profile cricket match between India and England, which meant many residents would likely be inside watching on television. The attackers also took advantage of the vulnerabilities identified during reconnaissance, which were exacerbated by the absence of patrol boats in the area that had been sent away to support an operation. These factors allowed them uncompromised infiltration.

Once ashore, the attackers split into five teams. Dressed in denim jeans, T-shirts, and Hindu religious wristbands, they easily blended in with the city’s residents and visitors. Each attacker carried a Western-style backpack loaded with a folding-stock AK-47 or AK-56 rifle, multiple pistols, grenades, dry rations, ammunition, and communication gear, which included satellite phones. Maintaining communications with their handlers in Pakistan was critical for several reasons. First, the handlers were monitoring live Indian news broadcasts and social media feeds, so they could provide real-time instructions throughout the operation and thus afford the attackers the ability to react to developments outside their targets. The communication also provided the attackers psychological support. The handlers were able to encourage the young, inexperienced militants to maintain their resolve and continue killing civilians and security forces by reinforcing their religious and financial motivations. During the operation, the handlers actively coached some of the attackers to continue shooting civilians and to hold positions against Indian security force responders.

The five teams moved toward their targets using planned routes. Two teams took taxis—one to the area near the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus and hospital, the other to the Oberoi Trident Hotel. Both teams left time-activated IEDs hidden within the vehicles that detonated after the drivers had departed both areas, adding to the chaos that was about to unfold. The remaining three teams moved on foot: one to the Nariman House, one to the Leopold Café, and one to the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel.

The Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus and Cama and Albless Hospital

Ajmal Kasab and Ismail Khan arrived at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus by taxi at 9:40 p.m. They were observed calmly walking through the station’s concourse and entering a public restroom, all recorded by surveillance cameras that Indian security personnel reviewed after the attacks. Despite the late hour, the station was still crowded with daily commuters, most of them heading home from work. Around 9:45 p.m., Kasab and Khan emerged from the restroom and immediately discharged bursts of automatic fire into the crowded terminal. Over the next twenty minutes the pair moved deliberately through the passenger halls and platforms, shooting commuters and railway employees and throwing grenades, killing fifty-eight and wounding more than one hundred.

Officers from the Railway Protection Force and Government Railway Police were first to respond, but armed only with .303 bolt-action rifles and 9-millimeter pistols, they were underequipped for the task. Police from the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus Police Station also arrived within minutes but were equally outgunned. Some officers engaged Kasab and Khan while others attempted to evacuate civilians amid the chaos. In one instance, a constable threw a plastic chair at the attackers in an act of desperation. Police Inspector Shashank Shinde, Constable Ambadas Pawar, and Home Guard Mukesh Jadhav were killed attempting to confront the gunmen. The lack of automatic firepower and limited range of their weapons meant they were no match for the AK-47 or AK-56 assault rifles being used by the terrorists. Despite the police officers’ best efforts, the attackers maintained fire superiority and freedom of movement, forcing the police to withdraw or sustain additional casualties.

At approximately 10:35 p.m., Kasab and Khan left the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus and moved southwest toward the Cama and Albless Hospital complex. Along the way, they fired on residents in the small structures near the hospital’s rear gate before scaling the rear compound wall. Once inside the grounds, they killed two guards and ascended into the tall building at the center of the compound, moving to its upper floors. Hospital staff, alerted by phone calls, texts, and sounds of distant gunfire, locked ward doors and ordered patients to shelter in place as the terrorists took elevated positions and intermittently fired into the surrounding area.

Commissioner of Police Sadanand Date, initially heading to the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, diverted to the hospital upon learning that the gunmen were now there. With six other officers, he took the elevator to the sixth floor, after learning the terrorists were holding several hospital employees as hostages on the floor’s terrace. Date reportedly exposed his position to draw the attackers down from the terrace to the sixth-floor landing, where a close-range gun battle erupted in the narrow space between the elevator lobby and the stairwell. The terrorists killed two police officers and injured Date and the other four. The terrorists then descended the stairs and exited the hospital compound.

A police contingent led by Anti-Terrorism Squad Chief Hemant Karkare, Additional Commissioner Ashok Kamte, Inspector Vijay Salaskar, and Police Officer Arun Dada Jadhav were on their way to the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus in a police Tata Qualis sport utility vehicle when they heard the reports from the police in the hospital. Now aware that the two terrorists had moved, the officers drove to the hospital to intercept Kasab and Khan. As they approached the hospital, Kasab and Khan ambushed them on a narrow road at close range and killed the three senior officers. Jadhav, who was seated in the rear of the vehicle, was struck by several rounds but survived by pretending to be dead in the back seat. It was now 11:45 p.m. After the terrorists drove for a short period and fired at personnel on the street, they hijacked and fled in another vehicle. After leaving the police vehicle, Jadhav radioed a message describing their new vehicle and the direction it was traveling: The attackers were heading west through the Dhobi Talao neighborhood. Reacting quickly, police moved to establish a checkpoint along the neighborhood’s Coastal Road near Girgaum Chowpatty public beach.

As Kasab and Khan continued their vehicle rampage, they fired at civilians and police, causing additional casualties as they drove west. At approximately 12:20 a.m. on November 27, the two terrorists encountered the police checkpoint. In the exchange of fire that followed, the police killed Khan, but they captured Kasab alive thanks to the brave actions of Police Constable Tukaram Omble. When the terrorists were forced to slow their vehicle at the checkpoint, Omble seized the barrel of Kasab’s AK-47, but in the process, absorbed a point-blank burst that killed him almost instantly. His actions, however, enabled other officers to subdue Kasab, who later became a central source of evidence regarding the attack and Pakistan-based facilitation behind it.

The Leopold Café

At approximately 9:30 p.m. two terrorists approached the Leopold Café. It was a well-known restaurant and bar in the Colaba neighborhood that drew both local patrons and foreign tourists. After pausing outside the café to possibly make a call on a mobile phone, the terrorists threw a grenade into the café and then opened fire on the crowded dining area. The attackers sprayed automatic bursts across the main floor, killing ten and wounding dozens more, shattering glass and scattering debris across the tiled floor. The terrorists proceeded to walk through the small restaurant spraying rifle fire. They tried to open a door that led to the second floor, but it was blocked by a table a customer had thrown down the stairs. The terrorists then exited a side door onto a side street and moved east toward their primary target, the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel.

While traveling toward the hotel, the terrorists continued firing at anyone they encountered, killing another thirteen civilians en route. They also placed a bag containing an IED with eight kilograms of RDX explosive on a side lane, near Gokul Bar on Tullock Road. Fortunately, the device failed to detonate and was later recovered and defused by a bomb disposal squad. The police control room received the first report about the attack at the café at 9:48 p.m., but it was initially assumed to be drug related or a gang altercation. Two police officers from the Colaba Police Station arrived within minutes and pursed the terrorists until sustaining injuries. A short while later, more police units arrived, but the attackers had already fled. The police evacuated the wounded and established a perimeter as emergency calls came to the police control room about attacks at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, the Oberoi Trident Hotel, and the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. The terrorists had executed the attack against the café in three minutes, but it had achieved its purpose of creating panic and confusion across this area of the city and immediately stressing the city’s already fragile emergency response network. Shortly thereafter, reports came in of taxis blowing up at Wadi Bunder at 9:56 p.m. and Vile Parle at 10:53 p.m.

The Oberoi Trident Hotel

At 9:20 p.m., two terrorists arrived by taxi at Nariman Point, a prominent downtown area that included the Oberoi Trident Hotel. The terrorists entered the lobby through a covered walkway and, within minutes, opened fire and threw grenades, killing guests in the Opium Den Bar, Brioni Shop, the computer server room, and the Tiffin Restaurant.

Police Inspector Bhagwat Kacharu Bansode of the nearby Marine Drive Police Station, who was on night patrol, received the first call at 9:51 p.m. and arrived within three to four minutes armed only with a revolver. Minutes later additional police units arrived. Upon entering the hotel, they discovered multiple casualties scattered across the lobby floor, but by this time the terrorists had moved up to a higher floor. The Oberoi Hotel is rectangular in shape with the entire middle open to the lobby below. This allowed the terrorists to remain hidden behind the railing of any of the hotel’s twenty-one floors until exposing themselves to fire or drop grenades on the lobby or lower floors.

At 10:15 p.m., an IED that the terrorists had dropped just outside the Trident Hotel exploded. Fifteen minutes later, another IED that they had dropped exploded outside the entrance to the Tiffin Restaurant adjacent to the Oberoi lobby.

The IEDs started fires that blocked the main corridors through the hotel’s atrium. Shattered glass, smoke, and falling debris made visibility nearly impossible. Additional Commissioner of Police K. Venkatesham established an outer cordon and traffic control while Additional Commissioner Vinay Kargaonkar led quick response team entries that managed to rescue at least seventeen trapped guests. At around midnight, Anti-Terrorism Squad Additional Commissioner Parambir Singh was directed to enter the nearby National Centre for the Performing Arts and Express Towers to engage the terrorists from elevated positions. From these vantage points, he identified and engaged one of the attackers on the eighteenth floor while attempting to contain the terrorists’ upper-floor movement. Attempts by the Mumbai Police quick response team and Anti-Terrorism Squad personnel to advance through fire exits were beaten back by grenades, automatic fire, and thick smoke.

At around 2:00 a.m. on November 27, eight Marine Commandos reached the Trident Hotel. Around 2:45 they moved to the third floor after hearing renewed firing, only to find that the terrorists had shifted positions. They then entered the Oberoi side through a side entrance, where they sighted a terrorist on the ninth or tenth floor. As they maneuvered upward they engaged briefly, but heavy automatic fire and grenade attacks from the upper floors stalled their advance.

At 8:50 a.m., National Security Guard counterterrorism commandos arrived from their base in Delhi and assumed control of clearing the building, with Marine Commandos assisting. Together they moved floor by floor, escorting civilians from stairwells and service corridors. The fighting and rescue operations continued throughout the day, and progress was slow in part because the National Security Guard lacked a schematic of the hotel.

At approximately 2:40 p.m. on the afternoon of November 28, the National Security Guard declared the fighting at the Oberoi Trident Hotel over, having killed the two terrorists. The terrorists had killed thirty people and wounded over twenty. The operation exposed the difficulties of simultaneous fires, narrow internal passageways, and limited knowledge of the building’s layout, which hampered early tactical responses and forced a cautious, floor-by-floor clearing that lasted nearly forty hours.

The Nariman House (Chabad Lubavitch Jewish Community Center)

The five-story Nariman House was located just a few city blocks southwest of the Leopold Café and the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel. Two terrorists arrived on foot and entered the building around 9:20 p.m., taking Rabbi Gavriel Holtzberg, his pregnant wife Rivka, and visiting guests hostage. The attackers quickly established firing positions overlooking the narrow lane leading up to the center and the buildings surrounding it. The police were slow to respond to the Nariman House because neither the local police nor the control room knew that a Jewish center was located there. When the first messages came in, the police did not understand where the attack was occurring. Reports of firing from “Colaba Wadi” in Nariman Point neighborhood added to the confusion until officers reached the scene and realized the target was the Nariman House.

Around 10:17 p.m., the first confirmed accounts of sustained gunfire from the area around the Nariman House were reported to the police. Shortly thereafter, Assistant Commissioner of Police Isaque Bagwan was directed to move toward the gunfire. He was the closest officer to the area, as he was currently located at the Leopold Café after having been dispatched there. Following the sounds of gunfire, he soon discovered that terrorists were in the Nariman House.

When Bagwan arrived, the neighborhood around the Nariman House was already in chaos. He quickly gathered the constables who had also just arrived and established a cordon around the building. He positioned the constables, armed with .303 bolt-action service rifles, on the rooftops of surrounding structures to keep the terrorists pinned until additional forces could arrive. At 11:30 p.m., a State Reserve Police Force unit reached the scene. With their help, Bagwan expanded the cordon and moved at least three hundred people out of the surrounding buildings.

Gunfire and explosions continued throughout the night and into the next morning. Around 8:00 a.m. on November 27, Indian caregiver Sandra Samuel escaped from the Nariman House carrying the Holtzbergs’ two-year-old son, Moshe. She confirmed to the police that hostages were still trapped inside. The police attempted to use tear gas to root out the terrorists, but they held their upper-floor positions, firing intermittently at any movement outside. National Security Guard commandos from Delhi finally arrived at 5:30 p.m. and took control of the site. They established a command post and began aerial reconnaissance using helicopters. They spent the night planning the rescue operation that would begin at first light.

At 07:30 a.m. on November 28, the National Security Guard commandos launched their assault on the Nariman House, conducting a helicopter rooftop insertion ascending down ropes onto the five-story building. Using close-quarters tactics and controlled demolitions, they cleared each floor from top to bottom. At approximately 7:45 a.m., the National Security Guard teams exited the building and reported that both terrorists were dead, as were all of the hostages—the terrorists had tortured the Holtzbergs before executing them. The operation at the Nariman House had lasted nearly forty-eight hours.

The Taj Mahal Palace Hotel

The attack at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel became the center of the most prolonged and publicized siege of the Mumbai attacks. The hotel is a sprawling, interconnected complex made up of the Heritage Wing, completed in 1903, and the Tower Wing, added in the early 1970s, which were linked through internal corridors, service passages, and back-of-house routes that create a maze-like interior. The Heritage Wing contained guest rooms, the grand staircase, the Chambers Lounge, private dining rooms, the Zodiac Grill, and multiple restaurants and banquet spaces spread across several floors. The Tower Wing included additional guest rooms, a modern lobby, and the poolside service entrance that opened into the hotel’s interior. Both sections contain narrow corridors, multiple stairwells, hidden service doors, staff-only elevators, and extensive back-area kitchens and utility spaces that allowed the attackers to move between floors and reposition without being easily tracked. Externally, the complex had several access points, including entrances on the Tower Wing that faced the waterfront and the Gateway of India, as well as the side entrance commonly referred to as the Northcote Gate, which opened near the pool and service drive. These design features gave the attackers both cover and freedom of movement once inside and complicated the ability of police, Marine Commandos, and the National Security Guard to locate, fix, and isolate them during the battle.

At approximately 9:44 p.m. on November 26, two terrorists entered the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel’s Tower Wing and moved into the lobby area, where they pulled out their rifles, opened fire on guests in the reception area, and threw a grenade. They then fired as they moved through the lobby and the shop-lined corridor, before taking a position at the top of the hotel’s grand staircase in the Heritage Wing, using the elevation to control the main entrance and observe movement down into the lobby. At nearly the same time, the two attackers who had struck the Leopold Café entered the hotel through the Northcote Gate and began firing indiscriminately at guests and staff in and around the swimming pool area. As these two moved through the pool and elevator area, they quickly linked up with the other two terrorists at the grand staircase to form a four-man assault team. Reports of the attack at the hotel immediately flooded the police call center.

Around 9:55 p.m., Deputy Commissioner of Police Vishwas Nangre Patil entered the hotel rear entrance with four or five policemen and hotel security manager Sunil Kudiyadi. Armed with pistols and .303 rifles, they were again no match for terrorists equipped with assault rifles and grenades. Yet, they advanced through the lobby under fire, evacuating civilians, and exchanging fire with the attackers while they moved. The terrorists used their elevated positions at the top of the grand staircase to their advantage, dropping grenades and pinning down the police. During this initial response, the terrorists killed Police Constable Rahul Shinde and wounded others.

By 10:30 p.m. the attackers had taken control of key sections of the hotel, including the Chambers Lounge and Zodiac Grill, where they barricaded themselves with hostages. They deliberately set fires to block entry routes and obscure their positions. Intercepted communications later revealed that the handlers directing the assault from Pakistan instructed the attackers to set the fires so that international media would capture images of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel in flames, turning the landmark hotel into a symbol of the attack. From the upper floors the terrorists fired intermittently at anyone in the courtyard or adjacent corridors.

At 12:46 a.m. on November 27, Deputy Commissioner of Police Patil, who had moved to the hotel’s closed-circuit television room after the initial firefight, made repeated radio calls requesting reinforcements, updating his headquarters on the attackers’ movements, and emphasizing the urgency of the situation. In one transmission he warned that “we are losing lives” and reported that hostages were being tied and moved to different rooms.

Around 2:30 a.m., a contingent of eighteen Marine Commandos arrived at the hotel and linked up with the police to assist in the clearing operation. About thirty minutes later, an Indian Army contingent reached the area and reinforced the expanding cordon around the hotel. At approximately 3:30 a.m., Marine Commandos engaged the attackers near the Chambers Lounge area and suffered two wounded. To keep from sustaining additional casualties, the Marine Commandos prioritized separating trapped guests from hostile areas and escorting civilians out through side exits and service corridors over eliminating the threat.

Between 3:00 and 3:45 a.m., multiple fires broke out, engulfing the upper levels and the iconic dome of the Heritage Wing. Joint Commissioner of Police K. L. Prasad coordinated evacuations, fire-suppression efforts, and the firefights with the terrorists on the upper levels of the hotel. Fire trucks that arrived attempted to extinguish the fires and evacuate nearly two hundred hotel guests with their ladders despite being under grenade and small-arms fire from the terrorists. Throughout the early morning hours sporadic gunfire, explosions, and flashover fires illuminated the building as security forces struggled to contain the inferno and locate the terrorists.

By dawn on November 28, the National Security Guard commandos from Delhi had finally arrived and were briefed on the situation by the police and Marine Commandos. Between 6:30 and 7:30 a.m. the National Security Guard commandos began methodical room-to-room clearing operations. It was a slow process made more difficult by fires, smoke, blocked passages, and the lack of a detailed schematic of the hotel. The terrorists had taken more than 150 hostages, killing many, while police, Marine Commandos, and the National Security Guard managed to rescue others as they advanced. Because of the hotel’s size and layout, clearing continued throughout the day and into the next, with long stretches of clearing empty rooms punctuated by sudden bursts of gunfire and grenade attacks as the terrorists fought from upper floors. At 8:50 a.m. on November 29, the Indian police declared the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel secured after the National Security Guard had cleared the entire complex and killed all four terrorists. In total, the attackers killed thirty guests, staff, and security personnel inside the hotel and wounded several hundred more.

The first strategic lesson learned is that urban warfare can be initiated by nonstate actors with little advance warning and that such attacks quickly draw the attention of senior political and military leaders. The threat to states, their most important cities, their security forces, and their citizens is not confined to border zones or peripheries. Cities are attractive targets because they are economic, political, and cultural centers. Protecting growing urban populations therefore requires commensurate increases in resources across surveillance, training, communications, transportation, and response forces. At the strategic level this means planners and political leaders must ensure the right forces, equipment, and funding are available and can be deployed rapidly when a city becomes a battlefield.

Another strategic lesson is that Pakistan’s long-standing use of proxy groups to wage covert war in India depends on maintaining plausible deniability—but that deniability was severely eroded when the Indians captured one of the assailants. The capture of one attacker, the interception of real-time communications during the assault, and later testimony from Pakistani-American David Headley provided compelling evidence that the attackers received training, support, and direction from elements operating within Pakistan. While no direct institutional link between Pakistan’s intelligence services and the attackers was ever conclusively proven, the accumulated evidence made official denials increasingly implausible. The public interrogation of the surviving terrorist exposed the cross-border coordination behind the attack, transforming what was meant to appear as an independent militant operation into a case of state-enabled terrorism. The broader lesson is that when proxies are captured or traced back to their sponsors, deniability collapses—and with it, the strategic leverage such covert operations are meant to achieve, making it best, when feasible, to capture rather than kill assailants.

The first operational lesson learned is the need for security forces to possess a deep understanding of the urban terrain in which they operate. Mumbai is too vast and complex for any single agency to know every street, building, and subterranean system, yet familiarity with assigned sectors can determine whether a response is effective or delayed. Regular patrols and sustained presence within specific districts allow units to develop a working map of the physical and human terrain, including key infrastructure, choke points, and access routes. During the 2008 attacks, the attackers’ prior reconnaissance and familiarity with the city gave them a decisive advantage. They moved confidently through slums, hotels, and transportation hubs while some of the local security forces initially struggled to orient themselves within the chaos. In urban warfare, situational mastery is not achieved during the crisis but through consistent preparation and terrain analysis long before it begins.

The second operational lesson is the need to be able to rapidly position skilled security forces where they are most needed to contain or neutralize threats. Mumbai presented multiple challenges that crippled India’s ability to provide a fast and coordinated response once the attackers struck several sites at once. The initial response fell to local police who were undertrained, poorly equipped, and unprepared for heavily armed militants. The city’s design, with narrow streets, choke points, crowded thoroughfares, waterways, and dense neighborhoods, further slowed movement and coordination. In retrospect, helicopters could have bypassed the congestion and inserted special security forces directly into active combat zones to blunt the terrorists’ momentum and force them to react. Instead of taking ten to twelve hours to reach Mumbai, the security forces could have been there in four hours (two hours to muster and a two-hour helicopter flight). This would have shortened the duration of the attack even if it had less of an impact on the total number of casualties.

The third operational lesson is the need for a unified and resilient command structure for security and emergency services to manage complex, multisite urban attacks. In Mumbai, multiple simultaneous attacks produced immediate information overload as reports arrived from the rail station, hospital, hotels, and the Nariman House, overwhelming call centers and senior leaders who lacked real-time situational awareness. With no single command authority to integrate intelligence, assign priorities, and direct resources, units acted independently, which resulted in duplication, delays, and uncoordinated responses across the city. These conditions exposed persistent weaknesses in India’s crisis management system, including limited interagency coordination, slow mobilization and deployment of national-level counterterrorism units, and the inadequate equipping of first responders who arrived at active combat sites without the weapons, protection, or training needed to contain heavily armed militants. Large cities facing fast-moving attacks require a centralized command architecture, common communications, and clear authorities so that key decisions can be made quickly and resources can be concentrated where they are needed most.

The first tactical lesson concerns how the attackers used the natural flows and noise of a megacity to move undetected through dense civilian patterns and exploit gaps across multiple layers of security. Their use of brightly painted local fishing boats, tourist clothing, Western-style backpacks, and religious wristbands allowed them to blend into the waterfront and the crowded streets after landing, and they timed their movement for night hours and a major cricket match when police attention was low. These conditions, combined with weak coastal patrols, unregulated traffic through Machhimar Nagar and the Sassoon Docks, and limited sharing of intelligence across maritime, police, and municipal agencies, allowed the teams to bypass early detection and reach major targets before security forces understood the scale of the assault. Major modern coastal cities require layered defenses that integrate maritime, police, transportation, and intelligence elements into a unified picture so that reconnaissance patterns, suspicious movements, and emerging threats are identified quickly and shared across all levels of security.

The second tactical lesson is the extent to which technology enabled the attackers to maintain real-time coordination with their handlers and adapt to the unfolding fight. The terrorists used GPS equipment and satellite phones to navigate by sea, track their progress to Mumbai, and communicate directly with their handlers in Pakistan throughout the assault. Intercepted communications later revealed that these handlers monitored Indian television coverage and gave tactical instructions based on live broadcasts, directing the attackers where to move, when and where to set fires, and how to prolong the siege for maximum visibility and psychological impact. This integration of satellite and media technology transformed the operation into a remote-controlled urban battle directed from another country. While many first responders exhibited courage under fire, they were severely outgunned and underequipped against a small, well-armed force supported by continuous external command and situational awareness. The lesson is that in modern urban combat, even a handful of fighters can use commercial technology to achieve effects once reserved for state militaries, blurring the line between local terrorism and transnational warfare.

The third tactical lesson is the danger posed by operational seams between maritime, military, and civilian security agencies and the need to close these gaps. In Mumbai the attackers converted detailed reconnaissance into an operational advantage by exploiting unclear jurisdictional lines and uneven surveillance across coastal patrols, port authorities, coast guard, local police, and national intelligence—allowing a small seaborne team to infiltrate, move ashore, reach their targets, and use back-of-house routes with little early detection. For national and local military and law enforcement authorities this suggests a set of high-level imperatives: recognize and map jurisdictional seams that an adversary could exploit; treat repeated foreign reconnaissance and extended, suspicious stays at sensitive sites as indicators, not anomalies; and view littoral approaches to dense urban centers as part of the same threat environment as the city’s interior. These are not tactical checklists but planning priorities—areas where improved clarity of roles, shared situational awareness, and anticipatory analysis can collapse the advantage that patient, technically enabled reconnaissance gives to a small, determined attacking force.

During the attacks, ten terrorists paralyzed a city of 17.9 million people for sixty hours. Across Mumbai, they killed 174 people and wounded more than 300. Indian security forces killed nine of the attackers and captured one alive. All the battles, but the battle at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel in particular, demonstrated how a small but determined force using the urban terrain effectively could outmaneuver and overwhelm a much larger force for days. The attack was also a good example of what can occur when even a small force conducts a good intelligence preparation of the urban environment followed by extensive planning and then conducts an attack using well-informed, well-equipped, and well-led forces. Conversely, it also offers an example of what can occur when defending security forces are not equally prepared.

The giant clouds of black smoke rising from the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel remain etched in the minds of Indians and many others who remember watching the attack unfold on live television. What began as a covert maritime infiltration ended as a sustained, multiday urban siege that would reshape how nations viewed both terrorism and the conduct of combat inside cities.

Liam Collins, PhD is the director of Madison Policy Forum and a distinguished military fellow with the Middle East Institute. He is a retired Special Forces colonel with deployments to Iraq, Afghanistan, Bosnia, the Horn of Africa, and South America, with multiple combat operations in Fallujah in 2004. He is coauthor of Understanding Urban Warfare and author of Leadership & Innovation During Crisis: Lessons from the Iraq War.

Major Jayson Geroux is an infantry officer with The Royal Canadian Regiment and is currently with the Canadian Army Doctrine and Training Centre. He has been a fervent student of and has been involved in urban operations training for over two decades. He is an equally passionate military historian and has participated in, planned, executed, and intensively instructed on urban operations and urban warfare history for the past twelve years. He has served thirty years in the Canadian Armed Forces, which included operational tours to the former Yugoslavia (Bosnia-Herzegovina) and Afghanistan.

John Spencer is chair of urban warfare studies at the Modern War Institute, codirector of MWI’s Urban Warfare Project, and host of the Urban Warfare Project Podcast. He served twenty-five years as an infantry soldier, which included two combat tours in Iraq. He is the author of the book Connected Soldiers: Life, Leadership, and Social Connections in Modern War and coauthor of Understanding Urban Warfare.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Anthony Albanese has appointed Dennis Richardson

to lead the review of intelligence and law enforcement agencies in the wake of the Bondi terror attack. The review will examine the powers and processes of the agencies and report back in April, with the findings to be published..

Dennis Richardson is not the person for that job given his past errors of judgement which include and which concern the Islamist Dr Waleed Kadous, and his wife Agnes Chong, whose history includes publication of the booklet Anti-Terrorism Laws: ASIO, the Police and You, which undermines anti-terrorism laws. Richardson was head of ASIO between 1996 and 2005.